Having devoted a good percentage of posts on this blog to news on the ravaging impact of the Ebola virus epidemic over the last couple of months, the varying degrees of successes achieved in containing the deadly disease in different parts of the world seems to point indispuatably but not entirely to the inequality in healthcare systems.

Now we know that Ebola had been in existence as early as nearly 4 decades ago, with outbreaks in Sudan and Zaire occurring between June and November 1976. But asides from laymen hearing of "Ebola" in some Hollywood movies or medical students reading a few lines about the disease in their medicine notes, not even the March 2014 outbreak in Guinea reported by the World Health Organization attracted any real attention either from the media or the World's biggest economies. It can easily be inferred by the closest observers that Ebola in Africa was not taken seriously until it entered into the commercial capital of one of Africa's biggest economies and one of the World's Biggest crude oil producing countries in Nigeria.

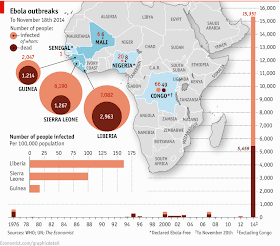

About a week following the entry of the Ebola-infected Liberian into Nigeria in July 2014, The WHO On 8 August 2014, the declared the epidemic to be an international public health emergency. Urging the world to offer aid to the affected regions, the Director-General said, "Countries affected to date simply do not have the capacity to manage an outbreak of this size and complexity on their own. I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible. This was after about 4 months of the disease ravaging the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia with death toll rising, about 1000 as at early August.

The truth is that the disease which is said to have entered into West Africa in December 2013, had unfortunately hit , "3 of Africa's Poorest economies" (to borrow the CNBC Africa headline from September 2014). The reality of this is that Ebola choose countries whose contributions to the Global Gross Domestic Product could easily be considered negligible by most. In a blog post in August "The Economics of Ebola",

The Liberian Finance Minister, cited the international aid of $200 million recieved via the specially set-up Ebola Fund established by the World Health Organization and World Bank in August to provide support for the 3 West African Countries. The question is how much attention would the the deadly disease have received if the countries affected were some of the region's biggest economies.

The disease however continues to have huge economic impacts even in this so-called poor economies with Ebola itself directly costing the governments of these countries increasingly. The factors contributing to the growing cost of Ebola include direct costs of the illness (government spending on health care) and indirect costs, such as lower labor productivity as a result of workers being ill, dying or caring for the sick.

But the majority of the costs stem from the higher costs of doing business within countries or across borders. These are largely due to “aversion behavior”, or changes in the behavior of individuals due to fear of contracting the disease, which has also left many businesses without workers, disrupted transportation and led to restrictions on travel for citizens from the afflicted countries.

According to the latest World Bank group report, if the Ebola epidemic is contained by the end of 2014, the economic impacts on West Africa, including on Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, could be lessened and economies would begin to recover and catch up quickly. If the crisis continues into 2015 as predicted, slower growth could cost the region $32.6 billion over 2014 and 2015 and lead to much higher levels of poverty.

There is no doubt that the inadequacies of the health-care systems in the three most-affected countries help to explain how the Ebola outbreak got this far. Spain spends over $3,000 per person at purchasing-power parity on health care; for Sierra Leone, the figure is just under $300. The United States has 245 doctors per 100,000 people; Guinea has ten. The particular vulnerability of health-care workers to Ebola is therefore doubly tragic: as of November 18th there had been 588 cases among medical staff in the three west African countries, and 337 deaths. The hope for these countries therefore lies in the hands of some of the world's bigger economies (who may not necessarily benefit in anyway from the epidemic stricken countries) to help their healthcare sysytem and invariably the "receeding" economy.

Refs: The Economics of Ebola (Medic-ALL blog)

The Economist

TheWorldBank.org